THEATRES OF POWER 1580-1780

Part One

Part One

You climbed the stairs to see the interior of an opulent palace, where you half expected to find Sleeping Beauty, reminding you of the toy theatre you played with when you were a child, its painted flats arranged layer behind layer giving you the illusion of depth and space, over which you had dominion, one of your first tastes of the enchantment of power.

Giuseppi Valeriani: Set of

designs for a stage set, 17th Century.

The Samuel

Courtauld Trust, The Courtauld Gallery, London

This pretty and delicate model was designed in the early eighteenth century as a seven piece set by the Italian Russian artist Giuseppe Valeriani with pen and brown ink, watercolour and judicious use of gold leaf on paper.

It was the starting point of the exhibition Stages and Scenes: Creating Architectural Illusion

at the Courtauld Gallery in 2008. The eight students on the Curating the Art Museum MA programme chose the piece before they had decided on a theme for their exhibition. Like a true fairy tale talisman, the object had powers of suggestion to open a door....

to the larger world.

to the larger world.

It was a modest exhibition of only 29 items, few of great artistic merit but all illustrating the young curators' grand thesis that "Through skilled rendering of architecture and perspective, the smallest stage can be converted into the most expansive of settings".

By making the connection between artistic experiments with perspective and the political propaganda of absolutism, Stages and Scenes gave a reflection of the illusions at the heart of state power in Baroque Europe.

The

inherently theatrical gestures and imagery

of Baroque art and architecture were adapted to meet the urgent need of

European states, destabilized from decades of ideological conflict and

political division, to restore order and redefine faith through a

coherent public image that could be felt, not just seen and heard.

The Roman Catholic Church reignited enthusiasm for the Counter-Reformation by offering an emotionally exciting religious experience in the new church buildings and biblical paintings. Secular regimes, hell-bent on centralization and legitimization of their often dubious right to rule, wooed their subjects with a glamorous, quasi-religious vision of their policies, disarming rational opposition with soaring vistas and dazzling tricks of the eye.

Architectural illusion was one of the most potent weapons in this charm offensive, and was used in the scenery of state opera and playhouses and in huge outdoor entertainments to promulgate and consolidate dynastic power, until the revolutions and Napoleonic conquests of the late 18th century swept away the old structure of patronage.

Rubens, Solomon Receiving the Queen of Sheba, 1620, oil on panel

© The Samuel Courtauld Trust, The Courtauld Gallery, London

© The Samuel Courtauld Trust, The Courtauld Gallery, London

The Roman Catholic Church reignited enthusiasm for the Counter-Reformation by offering an emotionally exciting religious experience in the new church buildings and biblical paintings. Secular regimes, hell-bent on centralization and legitimization of their often dubious right to rule, wooed their subjects with a glamorous, quasi-religious vision of their policies, disarming rational opposition with soaring vistas and dazzling tricks of the eye.

Architectural illusion was one of the most potent weapons in this charm offensive, and was used in the scenery of state opera and playhouses and in huge outdoor entertainments to promulgate and consolidate dynastic power, until the revolutions and Napoleonic conquests of the late 18th century swept away the old structure of patronage.

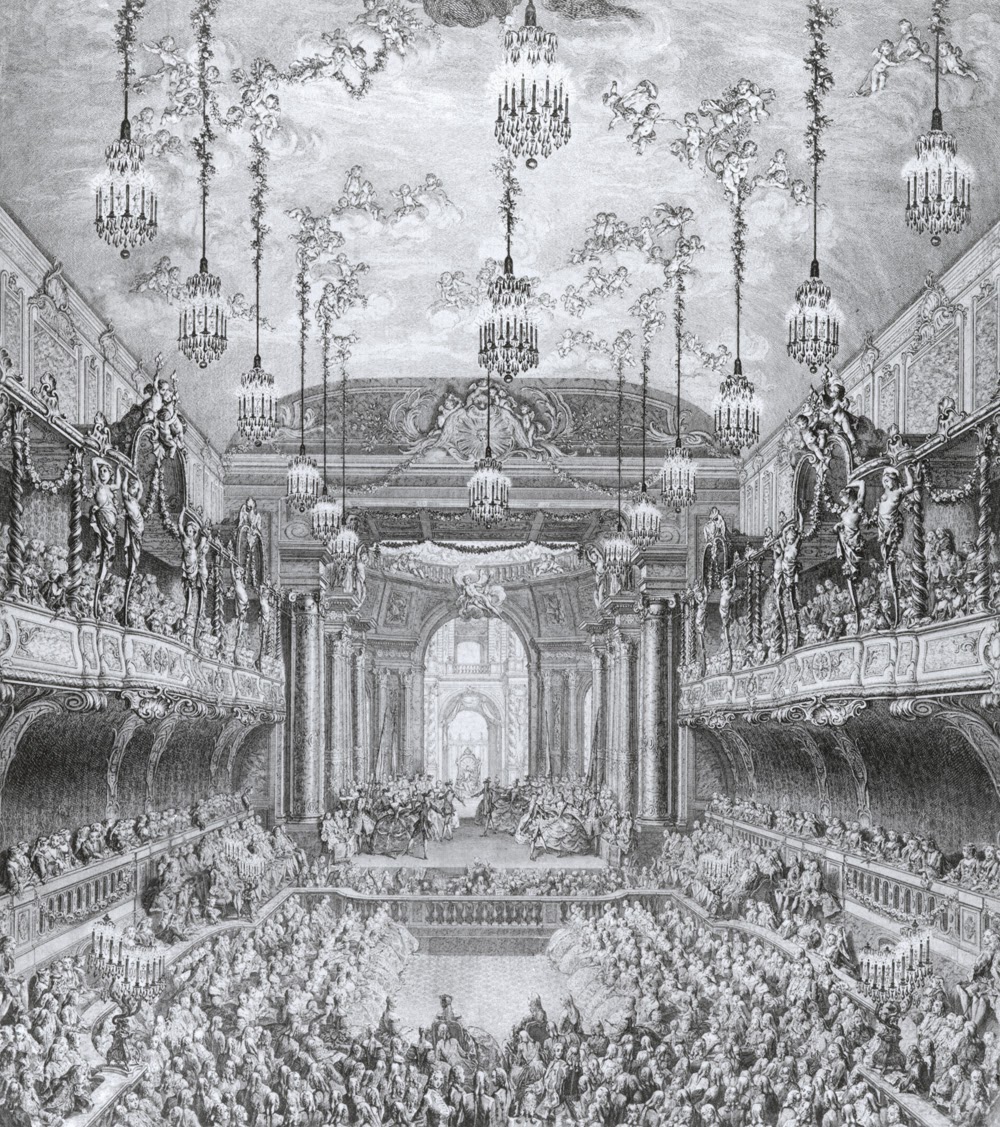

Ballet at Versailles, 1745, engraving by Charles Nicolas Cochin, of the performance of La princesse de Navarre, music by Rameau and words by Voltaire, in the Grande Écurie (the covered riding arena) of the palace. The first purpose-built theatre at Versailles, l'Opéra Royal, was opened in 1763.

Image © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

There were aesthetic adjustments to suit changing tastes, but baroque continued to be the preferred style of visual

communication long after the passionate drama of Rubens and Bernini was

sedated, and the subtle sensuality of Van Dyck coarsened by later

17th century artists, until it was superseded in the 18th century by the decorous elegance of

Tiepolo and the light-hearted scepticism of the Rococo, embarrassed by the

religious fervour and overt emotion of the past. Baroque reappeared in Romanticism, as the emotional, personal and rebellious counterpoint to neoclassicism.

Rubens' oil sketch on panel, Esther before Ahasuerus,

designed in 1620 for the ceiling of the Jesuit Church of Antwerp (the

decoration all destroyed by fire in 1718), one of the few paintings in

the exhibition, united the themes of architectural illusion and public display with dramatic figure-painting in glowing, sumptuous colours and

bold composition.

Here and in the accompanying scene Solomon Receiving the Queen of Sheba, featuring a show-stealing parrot, he used the equivalent of a telephoto lens effect of leading our eyes upward at a vertiginous perspective, to catch a glimpse of dramatic interaction of characters standing between palatial columns and staircases under looming arches.

Rubens, Esther before Ahasuerus, oil on panel, 1620

Copyright: © The Samuel Courtauld Trust, The Courtauld Gallery, London

Here and in the accompanying scene Solomon Receiving the Queen of Sheba, featuring a show-stealing parrot, he used the equivalent of a telephoto lens effect of leading our eyes upward at a vertiginous perspective, to catch a glimpse of dramatic interaction of characters standing between palatial columns and staircases under looming arches.

Rubens'

bravura technique is easy to dismiss as vulgar and commercially superficial, his

fleshly obsession verging on the pornographic, distracting attention

from the thoughtfulness of his compositions and the expressiveness of

his figures. Their gestures and faces are caught with operatic intensity in the very moment of

emotion, not in tranquillity before or afterwards, involving us all in a human story of love and passion, rather than political and economic self-interest.

PART TWO

coming soon

coming soon

© Pippa Rathborne 2014

Adapted from an article published as Exhibition Review | STAGES AND SCENES

on Rogues and Vagabonds Theatre Website in 2008, with permission of Sarah

Vernon and with many thanks to The Samuel Courtauld Trust, The Courtauld

Gallery, London for permission to use images from their collection.